I: Many paths through

In a long conversation with a friend, we started pitching startup ideas. We quickly realized that while we were both trying to solve meaningful problems, we had arrived at our ideas in completely different ways.

One of us started with a vision: a product idea that felt obvious and inevitable.

The other started without a clear vision, but found a problem through user interviews and iterated to build a solution.

We also noticed how each of us were supported by conventional wisdom, yet each piece of wisdom contradicted the other. Like how patience is a virtue but the early bird gets the worm.

One common belief is that entrepreneurship is a creative act, where a visionary founder forces their will on the world. Call this the Zero to One school of thought.

“From 0 to $10 million, you have to be very dictatorial. You tell people what you want, people will tell you ‘this isn’t going to work.’ Ignore comments, you ignore feedback, and you do what the hell you want.”

- Ben Francis, Gym Shark founder & CEO

The iPad is a great example. At first, it seemed like a niche product serving no real need. Yet a clear vision delivered it to incredible popularity; redefining its product category. Same went with AirPods.

Both Apple and Gym Shark had founders with such deep grasps of their domains that not only were the problems obvious, but the solutions too, and far before anyone else could see.

Another take, the Y Combinator school of thought, is to find pressing problems by talking to potential customers and identifying their issues, even if that takes co-working with your clients.

In this view, rather than having a vision you just need enough vision to see problems as they arise and be capable enough to solve them.

Many YC admits I know were accepted contingent on giving up the idea they pitched and finding a new one by speaking to potential users.

It’s clear there is not one correct way to find a startup idea. But the way you search dictates what you can find. The real mistake is defaulting to a search strategy unconsciously, because you won’t realize how narrowly it’s shaping what you see.

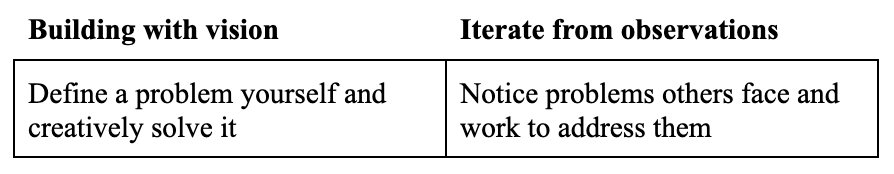

Our framework so far:

Reflecting on our search process, I remembered an experience I had in the rainforest.

II: The jungle teaches us how to search

I spent a few days in the Amazon while visiting Ecuador with friends. We stayed at a small jungle lodge, met local community members, and explored the rainforest by canoe.

On these river trips, we were constantly amazed by how easily our guides spotted animals: monkeys, sloths, river dolphins. It seemed impossible.

“I don’t get it,” one of us said. “It’s like the animals are animatronics, and the guides just memorized where they’re placed.”

Each sighting baffled us more. Every animal lived differently, moved differently, hid in different places. The randomness made it feel like magic. We did not understand their search algorithm.

One evening, we boated to a large lagoon to watch the sunset. The night fell.

As we returned, our guide began looking for animals as they always did. But now, they used a flashlight. Unlike before, we could now directly follow their gaze, that cone of light, side, side, straight up-down, side, side… The search algorithm we’d wondered about was clearly legible.

We had thought that if we saw an animal, we would know how to look for it in the future. That was disproven when our guide showed us a sloth and we never found one after. So discovering an animal once wasn’t what revealed how to find it again, rather we had to witness how others discovered them to even give us a chance.

The nighttime boat ride revealed something new: not just the narrow discovery of one particular search algorithm, but also the broader finding that specific circumstances can uncover new search algorithms.

Another guest had asked the guides how they spotted animals. The answer? A vague, confusing explanation. Turns out, some search algorithms can’t be explained.

III: Flashlights and cargo cults

While it’s a simple idea, the outcome of a search depends on your process.

Before we saw the flashlight at work, our eyes scanned from the river basin to the treetops without much to show for it, even though we knew what the animals looked like. Same with startups. Knowing what a billion-dollar company looks like doesn’t teach you how to discover one.

Each search algorithm could be bad business advice; something promising that worked for someone else but does not apply to your situation. Airbnb was founded because they struggled to pay rent and had an air mattress, that search algorithm surely just works once.

When you learn about somebody else’s search algorithm you risk “cargo culting” it; imitating the practice without understanding the underlying reason it works. Cargo cult businesses are doomed to fail because they don’t solve real problems for real people.

As my friend and I discussed how we found ideas, we realized we had been borrowing search algorithms from so-called best practices without questioning if other strategies might exist.

Our framework wasn’t complete.

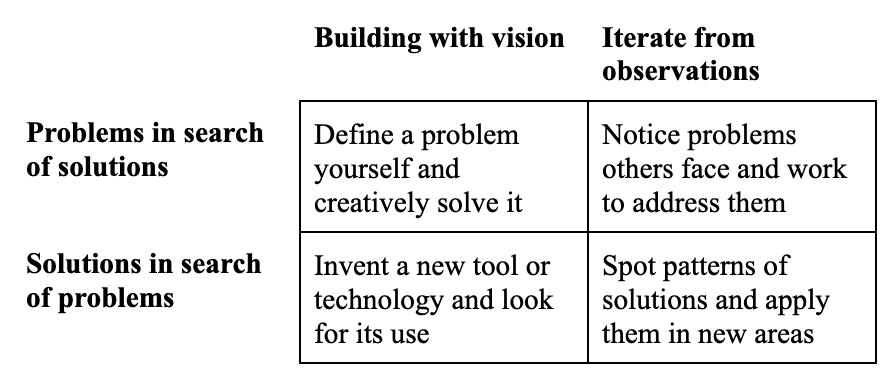

Building with vision or iterating from observation is just one axis. Both cases still started with a problem and worked toward a solution.

But what if we flipped it? What if we started with a solution instead?

IV: Solutions in search of problems

Most startup advice says: “don’t build something nobody wants.” Solutions in search of problems are a classic mistake.

Why? Because without real demand you waste time and money on chasing a market that doesn’t exist. You never find product-market fit.

But that logic doesn’t always hold. OpenAI started with no product, no customers, no clear business plan. Just a bet: automating intelligence would matter someday. Real use cases emerged over time. They found demand by backing into it.

Technologies like the internet, GPS, and lasers started with niche use cases. They later sparked massive consumer demand and often unexpectedly. Uber? Before smartphones and GPS, no one was asking for rides on their phones. But those tools made it inevitable.

An idea’s ability to apply beyond its original context, or its reach, is important when considering solutions in search of problems.

Reach matters because a solution must eventually find a problem worth solving; and the reach of an idea determines whether it will still apply when it does.

A specific idea’s reach is normally only seen retrospectively. However, we can still explain why ideas generally “reach” into the future:

They solve evergreen problems that persist beyond trends or locations; like communication, transportation, or energy.

They enable exponential improvements through cutting costs, accelerating processes, or scaling distribution to make goods possible or affordable for the first time. Cloud computing, for example, opened powerful infrastructure to many more users.

They leverage network effects or platforms, starting small but growing as each new user adds value, until they eventually reach massive markets; like social networks or marketplaces.

These weren’t just solutions in search of problems. They’re bets on the future grounded in tech potential or societal change.

There’s another kind of solution-first startup and it's one that looks at patterns and asks: “where else could this work?”

V: X for Y

Solution transposition: taking a successful model (X) and applying it to a new, unexpected domain (Y). Think:

“It’s like Netflix, but for online courses.”

“Uber, but for laundry.”

“Airbnb, but for RVs.”

This model works when two conditions are met: (1) the original solved a real problem, and (2) the new domain has similar dynamics or points of friction.

In other words, the old solution has “reach” into whichever new domain it is applied to.

Copying business models often fails when founders don’t understand why the originals worked. But if you deeply understand both the original idea and the new market, you just might succeed.

Uber to Postmates/DoorDash: real-time logistics and on-demand service applied to food and package delivery.

YouTube to MasterClass: streaming video meets premium education.

Tinder to Bumble/Hinge: swipe mechanics adapted to new social values and user intentions.

Poor transpositions are common, not because the approach is flawed, but because people skip (or simply mess up) the hard part: understanding why the original solution worked and whether those conditions exist in the new market. A successful transposition doesn’t just copy form, which creates a “cargo cult startup,” but it also maps function.

Scaffolding means nothing without something to scaffold.

Many founders fall into the same trap we did in the Amazon: seeing something once and assuming they know how to find it again. But ideas don’t repeat like that.

When you transpose an idea, you must re-run the search algorithm, not just reuse the answer key.

VI: The shape of the jungle

Originally, our framework was confined to “problems in search of solutions.” We didn’t realize that was a blind spot.

It took a specific moment, like the sun setting in the Amazon, to shift our perspective. Reflecting on our different approaches revealed valid search algorithms we had dismissed, and not because they were unknown, but because we had assumed they were wrong.

In reality, there are good explanations why those other strategies sometimes work and will work again. The mistake was not in their use, but in our unexamined rejection of them.

When we first built our framework, we thought we covered the full landscape of how ideas form. We thought our “idea search algorithm” search algorithm was complete. Yet now, the jungle’s shape had changed:

Just as nightfall revealed the search algorithm through the flashlight’s beam, unexpected moments expose hidden search methods to you.

This matrix is not a map. It’s incomplete and destined to be subverted.

Startup ideas are likely too complex and dynamic for any one framework to fully capture.

The real advantage founders can gain is not from having one “right” algorithm (or one right algorithm framework) but from recognizing the search they’re using, the limitations it has, and being ready to adapt or switch it as they learn more.

That awareness turns random wandering into deliberate exploration.

Satisfied with this “business idea matrix,” I began testing it through conversation.

VII: A specific circumstance

Someone saw an issue.

Their friend recently launched a successful startup that wasn’t visionary, wasn’t based on deep user research, and wasn’t even a novel application of an existing model. It was, quite simply, a copy. The same X for the same Y.

Copying had no slot in the matrix. But that’s because the framework assumes you need to find a differentiated idea.

They proposed the flipside: differentiated execution.

I paused. The boundary between execution and ideas is a careful one. It appeared the two could blur.

Some founders claim “it's all about execution,” but that skips over the fact that great execution often stems from a belief, a hunch, or a specific insight that others missed.

Take “copycat” stories: Rocket Internet, Didi, even Facebook. They were executing existing concepts, but not blindly. Their “copying” was informed by a differentiated idea:

“I think consumers in this market want the same thing, but done better, faster, cheaper or tailored to them.”

That belief is, in itself, a kind of idea. Not a radically new product or market, but a thesis about unmet expectations within an existing model.

We tend to give more credit to visionary leaps: founding a category, inventing a technology, creating something no one imagined. But in truth, many billion-dollar companies started with simple ideas: "I think this can be done better for this audience, I think the original team missed this, I think timing, tools, or behavior has shifted, and now this works.”

These are forms of differentiated thinking.

In other words, my friend was incorrect.

“Better execution” is never just execution because it reflects a belief about what dimension actually matters.

“Better” must in fact be better along some dimension and choosing which dimension to improve on is a strategic idea found using a search algorithm.

So when someone says, “It’s all about execution,” what they often mean is:

“We picked the right lever to pull and we pulled it hard.”

That lever, the dimension of differentiation, is the real insight.

In the Amazon, we thought seeing an animal once meant we’d know how to find the next one. But it didn’t. What helped us improve was not the sighting, it was watching how the guide searched. The flashlight revealed the method.

This story was no different.

They thought they were seeing a simple copy of a business. But they missed that it was instead someone using a different flashlight: choosing a specific dimension to out-execute on, based on a belief about what mattered most in that market.

In hindsight, it followed the same pattern: Missing the search algorithm because it didn’t look like a search. It looked like copying, but was actually a kind of discovery, only hidden behind the word “execution.”

They weren’t cargo-culting someone else’s success. They were re-running the search with a new method of seeing.

The jungle isn’t just filled with hidden animals; the things you want to search for. It’s filled with hidden algorithms; with ways of searching.

In the end, what you find depends entirely on how you look.

And sometimes, the real discovery isn’t what you saw. It’s how you learned to see.

Great piece, really demystifies the difference between 0→1 and N→1 innovation. I think it’s important to recognize that N→1 isn’t just execution; insight and belief drive fast followers too, which makes it just as valuable as 0→1.